For almost three years now (since the beginning of the Covid crisis), European agriculture has been dealing with one challenge after another and one crisis after yet another one. The cumulative consequences of these challenges continue and, even increase, when they are not anymore at the headlines. And this will be a serious threat on European agriculture – and on global food security – for the months to come.

During the Covid pandemic, farmers organised themselves to ensure a supply of quality, quantity in time to all Europeans as well as to third-party markets. In order to bounce back from the market closure linked to this period, the European Commission had proposed to include a €20 billion package for agriculture within its European recovery plan. But the Heads of State and Government finally decided on a narrow envelope, reduced by more than half of the initial amount (8 billion). This reduced package gave a fairly large flexibility of use for the Member States. In fact, a very small fraction have been used to finance recovery investments.

Nonetheless, the economic effects of the health crisis have persisted for economic actors with increased costs of inputs and intermediate consumption under the dual effect of a recovery in world consumption and bottlenecks among suppliers, primarily in Asia. This increase in production costs was only very partially passed on to the downstream sector. It weakened the margins of the agricultural sectors and farmers.

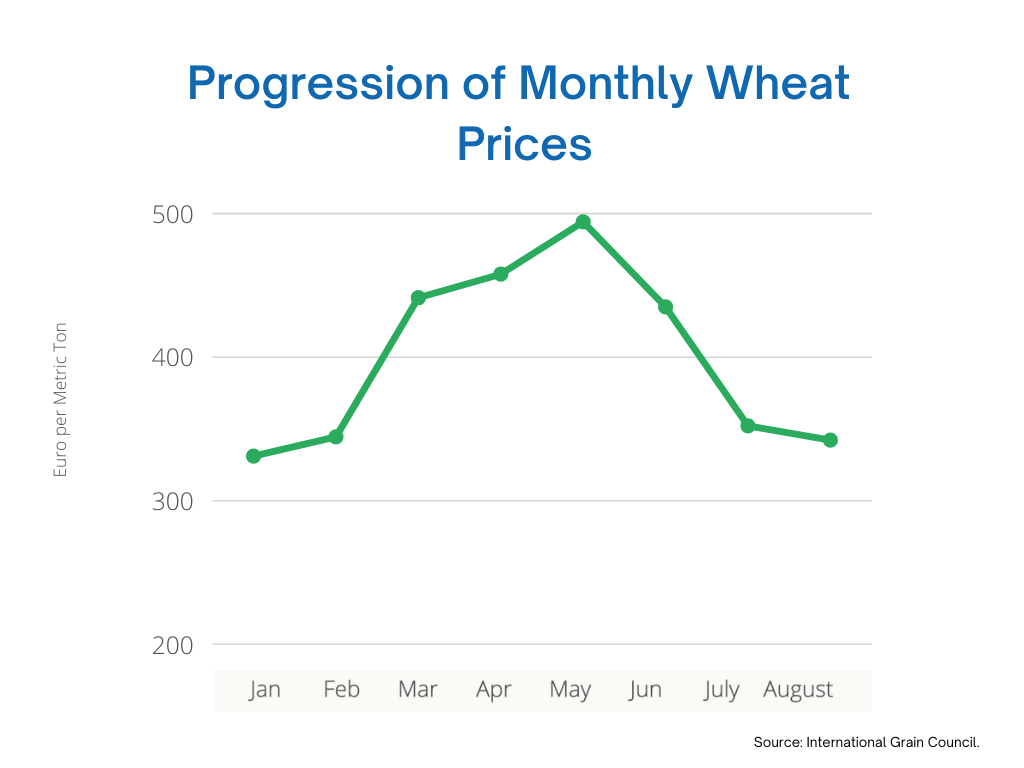

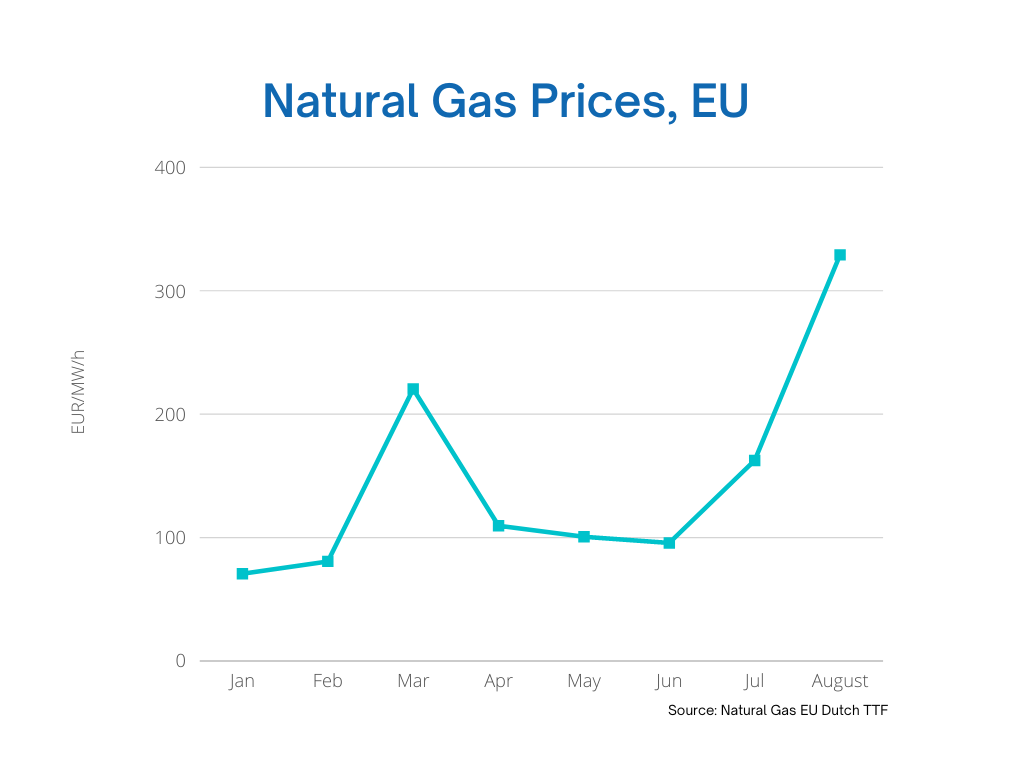

From autumn 2021, the worsening of the situation between Russia and Ukraine created tensions over energy prices. It turned into a deep crisis with Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. The blockade of Ukrainian ports and fears about food security led to price spikes for agricultural products. These increases in agricultural prices were only marginally passed on to farmers, as the majority of field crop production had already been sold or contracted out beforehand. Traders were the main beneficiaries. When it comes to livestock production, the rise in food prices annihilated any potential positive effect of price increases.

Today, agricultural prices are tending towards the pre-invasion levels of Ukraine. However, input prices, especially for fertilisers, remain extremely high, linked to uncertainties on the gas market. Neither these, nor the announcement of the closure of fertiliser plants in Europe, point to an easing of the situation. While the drop in global agricultural prices may divert the spotlight from the fundamentals of agricultural markets, the fear of an EU agriculture struggling against the consequences of such a price squeeze is real.

In order to limit the impact of the Ukrainian crisis on European agricultural production, the European Union has allowed Member States to act in a scattered manner, depending on their ability to mobilise national budgetary resources. 9 Member States have submitted state aid measures for their agriculture since April 2022 (Germany, Poland, Italy, France, Estonia, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Austria, Bulgaria) with important gaps in the level of support generating frictions on the internal market.

These measures, for those who have been able to benefit from them, are likely to alleviate some of the current difficulties, but they do not anticipate the scenario that is taking shape of falling market prices and production costs remaining at their peak.

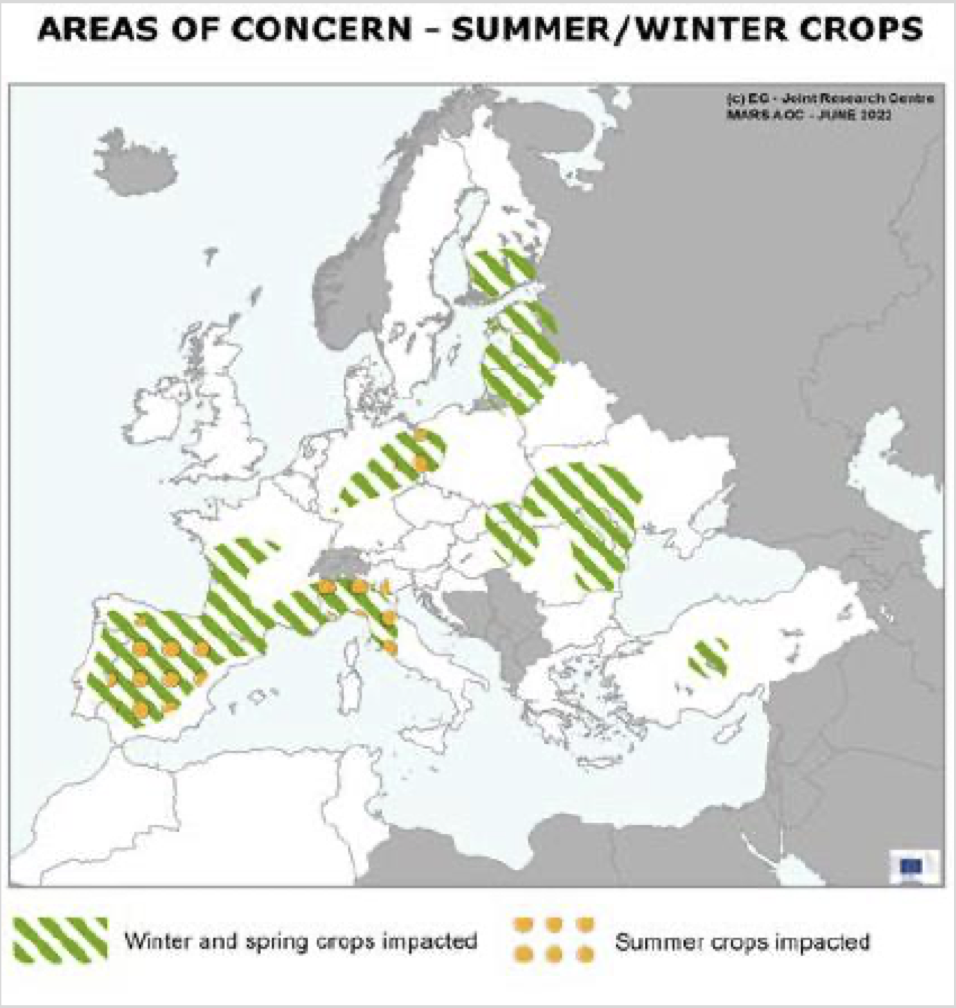

At the same time, the European Union has experienced one of the worst droughts. 14 of the 27 Member States were severely affected (Portugal, Italy, Spain, France, Ireland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Croatia). Apart from rapeseed production, other crops are down, making farm accounts even more fragile. As for fodder production, it is in a very worrying state and is threatening the survival of many farmers. Already struggling with the rise in feed prices and other production factors due to the war in Ukraine, they are now faced with a need for fodder that they may have great difficulty in meeting by the autumn. Under such conditions, decisions to decapitalise are to be anticipated, with the corollary of an imbalance between supply and demand that could lead to a reversal of prices and a downward spiral.

When it comes to production in 2022/23, no sector seems to be immune to declining turnover & rising production costs; neither the animal nor the plant sectors. In fact, it is in the coming weeks that the ability of European agriculture to ensure the smooth functioning of the markets (European and for its share of responsibility for the supply of world markets) for the next 18 months will be at stake. The decisions to pay CAP aid in advance are a one-off cash flow aid, but will not be enough to break the spiral. Faced with a situation such as the present one, the maintenance of the European productive potential and of farmers at the forefront of our food security necessarily requires reductions in charges and financial aid (from fresh funds) to be decided and implemented urgently.

The Parliament and Commission return after the summerbreak must be the time for action, action for a Europe standing by its farmers.

O artigo foi publicado originalmente em Farm Europe.